LS1 - Order of the Million Elephants and White Parasol

LS4 - Medal for Excellence in Education

LS6 - Order of Agricultural Merit

LS7 - Medal for Military Valor

LS9 - Medal of Government Gratitude

LS10 - Order of Feminine Merit

LS13 - Franco-Laotian Resistance Medal

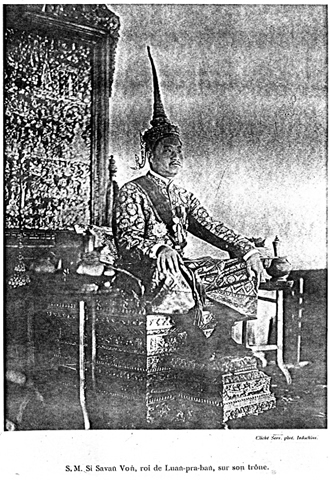

King Savang Vatthana

(Wearing the Collar and Star of the Grand Cross of the Order of the Million Elephants and White Parasol, the Order of the Reign, the Order of the Crown, the Medal for Excellence in Education, the Order of Agricultural Merit, and the Order of Civil Merit)

The Kingdom of Laos, and the Mekong Backcountry

Laos – Lan Xang Hom Khao (The Land of the Million Elephants and White Parasol) – was divided in the 18th and 19th Centuries into the three kingdoms of Luang Prabang, Vientiane, and, in the south, Champassak. The stronger Siamese monarchs maintained suzerainty over these kingdoms. The Vietnamese on the other side of the Annamite Cordillera also had lingering claims, to be assumed by the French.

In 1885, when the French began to be interested in extending their sphere of influence over Laos, Chao Kham Souk was ruling in Champassak and Oun Kham in Luang Prabang. France secured the permission of Siam to establish a Vice Consulate in Luang Prabang under Auguste Pavie, who was to become the father of the French presence in Laos. In 1887, after a withdrawal of Siamese troops, Luang Prabang was sacked by the T'ai minority leader Deo Van Tri and the Red Flag and Ho bandits. Pavie's assistance to King Oun Kham during this period put the Lao in French debt. Thereafter, the French in successive stages, which included a show of naval force at Bangkok in 1893, forced Siam to relinquish its claim to Laos. Pavie was named Commissioner General. Oun Kham was succeeded by his son Sakarine in 1888, and he in turn by Sisavang Vong in 1903.

In 1899 the two regions of Upper and Lower Laos, then under separate military commandants superior, were combined under a resident superior. In 1905 Siam relinquished its claim to the territory of Bassac on the right bank of the Mekong. The King of Luang Prabang, as detailed later under the Franco-Laotian Convention of 1917, ruled over the provinces of Luang Prabang and Samneua and the Fifth Military District of the highland country. The regions of Vientiane and Champassak were directly administered by the French authorities, although with recognition of the Champassak royal house. Laos was governed largely by French and Vietnamese officials and was lightly garrisoned by French colonial troops and policed by the Garde Indigene, a native constabulary.

Following the Japanese coup de force, King Sisavang Vong was pressed to declare independence on April 8, 1945. Prince Boum Oum of Chapassak took the lead of an anti-Japanese nationalist movement. A second nationalist movement, the Lao Issarra, was anti-French and centered around Vientiane. The Lao Issarra, who combined both leftists and non-leftists, raised a number of battalions and tried unsuccessfully to prevent the return of the French after the Japanese defeat. The Chinese also occupied Laos down to the 16th parallel, but they withdrew in 1946.

In a move partially to appease the nationalists, the French in a provisional Modus Vivendi of August 27, 1946, agreed to the unity of Laos under King Sisavang Vong, with Boum Oum under a secret protocol made the hereditary Inspector General of the Kingdom. A General Franco-Laotian Convention of July 19, 1949, specified the independence of Laos within the French Union. The Franco-Laotian Treaty of Friendship and Association of October 22, 1953, continued the process, which was completed de facto in 1954 as the French officials and most of the French forces departed, leaving a small advisory mission.

The Geneva Agreement for the cessation of hostilities in Laos of July 20, 1954, was intended to make Laos a neutral buffer state. The Viet Minh armies had struck into Laos in 1953, and at the time of the agreement were in control of Samneua and Phongsaly provinces. The political divisions were unresolvable, however, and the rightists in 1958-9 moved against the Pathet Lao and ousted the neutralist Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma. In August 1960 the parachute battalion commander Kong Le led a coup against General Phoumi Nosavan that left a shot up Vientiane and a neutralist army squeezed between the two others. The Geneva Conference of May 1961 moved to avert an international crisis over Laos. Souvanna Phouma returned to head a new coalition government, from which the Pathet Lao representatives soon departed. Laos then increasingly became enmeshed in the Vietnam War as the People's Army of Vietnam used eastern Laos for their transport network to the south and consolidated their position around the Plain of Jars. The US Air Force was heavily used against them.

Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma of Laos

In 1954 the Royal Lao Army – called by themselves Kang Thap Haeng Sat, the Army of the Nation – had consisted of 14,500 personnel, largely French officered, in six infantry, seven light infantry, and one parachute battalions, plus some 6,500 poorly trained National Guard. There were some 7,000 Laotians still in the French units in eight Bataillons Chasseurs Laotians. They often were in rivalry with the Royal Lao Army officers and men.

Charge McClintock in a 1954 Embassy Saigon cable on the possibilities of local armed forces had commented: "In Laos, human material is exceedingly weak as Laotians merely wish to live and let live and have no national ardor." But, despite skepticism, the US tried hard to build a modern army. In 1961 the army had 40,000 men in 20 infantry battalions, 30 plus volunteer regional battalions, 12 artillery battalions, and a small air force and riverine navy. The five military regions largely ran their own separate wars. Cynical observors described the Royal Lao Army as more of a business firm than a military force, and top commanders did grow rich from their positions. An exception was the Armee Clandestine of General Vang Pao. This 20,000 man force of minorities of the northeast was supported by the CIA and fought bravely in defense of their mountainous homeland. By the end of the war the bloodletting had left few of their officers who had long experience. The Royal Lao Army regular units also, however, did see much combat in the course of the long war.

In 1973-74, reflecting again events in Vietnam, a ceasefire was declared and a Provisional Government of National Unity formed from the "Vientiane side" and the Pathet Lao. In 1975 the Communists moved to consolidate a victory in this last portion of Indochina, and the Lao elite fled as best they could. King Savang Vatthana, who had reigned since 1959, was forced to abdicate and sent to a samana ("seminar" or re-education camp) to die.